South Africa’s jazz history is nearly as old as America’s, with jazz-influenced performing emerging in urban centers like Johannesburg in the early 20th century. Featuring a big band tradition and a variety of regional styles, South African jazz has a unique set of standards and a rich array of innovators, many of whom harnessed jazz in the battle against South Africa’s apartheid system. We celebrate the history of South African jazz with these essential records.

Jazz Epistles, Verse 1

Though it may have been short-lived, the Jazz Epistles were a South African Jazz supergroup if ever there were one. Both a young Hugh Masekela and a young Dollar Brand (later Abdullah Ibrahim) served in the group, alongside trombonist Jonas Gwangwa, bassist Johnny Gertze, and drummer Makhaya Ntshoko. At the center and heart of it, though, is altoist Kippie Moeketsi, the godfather of South Africa’s modern Jazz scene, and the mentor to many of these artists. His solos on this album of original works, particularly “Scullery Department,” rank among some of the greatest put to record.

Miriam Makeba and the Skylarks, The Best of Miriam Makeba & The Skylarks

While Miriam Makeba may be best-known for her 1960s recordings, particularly of “Pata Pata,” these recordings from the 1950s rank among the finest in her career. Still a rising star at the time, Makeba had come to prominence by singing with the leading close-harmony vocal group of the day, the Manhattan Brothers. Gaining enough notoriety of her own, Makeba went into the studio with an all-women vocal group—a rarity at the time—called the Skylarks. The results stand as some of the finest examples of this style, and the recordings also highlight Makeba supremely confident and swinging, a master vocalist even at the dawn of her career.

Abdullah Ibrahim, Mannenberg – Is Where It’s Happening

Although Abdullah Ibrahim (formerly Dollar Brand) had left South Africa for Europe and then America in the 1960s, he returned to South Africa at points in the 1970s. During those visits, he would record some of the landmark albums of his career with a host of incredible local talents. No recording, however, stands out more than Mannenberg – offering up two long tracks—the title track and “The Pilgrim” are each about 13 minutes long—the album calls back to an earlier form of South African Jazz. With this album, Ibrahim captured lightning in a bottle, inadvertently creating an unofficial anthem for the youth uprisings that would occur just a few years later. The performances on this album are iconic: Robbie Jansen’s and Morris Goldberg’s alto solos still sound fresh four decades later, and Basil Coetzee’s tenor solo was so extraordinary and influential that he began to go by the nickname “Mannenberg.” By the way, if this song doesn’t ring a bell, you might know it by its American release name, “Cape Town Fringe.”

Hugh Masekela, Home Is Where the Music Is

“Grazin’ in the Grass,” “Stimela,” and “Bring Him Back Home (Nelson Mandela)” were undoubtedly bigger hits for Bra Hugh, but the tracks on this 1972 masterpiece represent some of the greatest playing he would do in his career. Paired with exceptional compositions and a truly amazing band—fellow South Africans Dudu Pukwana and Makhaya Ntshoko alongside Larry Willis and Eddie Gomez—Hugh Masekela offers up an album that is simultaneously catchy, grooving, yet also heart-wrenchingly moving.

iTunes | Spotify | Apple Music

Bheki Mseleku, Celebration

For many listeners, pianist/composer/saxophonist/vocalist Bheki Mseleku stands as the greatest musical genius South Africa ever produced. A onetime member of innovative 1970s mbaqanga-fusion ensembles like The Drive and Spirits Rejoice, Mseleku ultimately left for Europe. By the 1990s, he had established himself as a musical force to be reckoned with, and with the 1992 release of Celebration, he made it clear that he was a talent without peer. Joined by master artists like Courtney Pine and Marvin “Smitty” Smith, Mseleku burns through Coltrane-infused original works, offering fiery improvisation that sometimes bursts out from his structured, tightly organized compositions. While the album’s highlight for many is the track “Angola,” the closing duo interplay between Mseleku and Pine on “Closer to the Source” is something that must be heard to be believed.

iTunes | Spotify | Apple Music

Zim Ngqawana, Zimphonic Suites

With the end of apartheid in 1994, South Africa saw a burst of creative energy in its Jazz scene, as a new generation of artists sought to explore global music cultures, while also exploring and celebration their own musical traditions in a manner unencumbered by the strict rules of the apartheid-era South African Broadcasting Corporation. One such artist was saxophonist Zim Ngqawana. Hailing from the Eastern Cape, Ngqawana studied Jazz at the University of Natal (later University of KwaZulu-Natal). He soon showed a truly fascinating vision for the music, drawing on traditional Xhosa cultural practices, and finding a fusion between them and the modal music of Coltrane-era Jazz. On Zimphonic Suites, Ngqawana kicked his writing and playing into a new level of ambition, crafting an incredible set of extended-form works that explore this space.

iTunes | Spotify | Apple Music

Moses Taiwa Molelekwa, Genes and Spirits

Another artist to emerge in the 1990s post-apartheid Jazz renaissance in South Africa, pianist Moses Taiwa Molelekwa embodied an extraordinary international vision for what South African Jazz could be. On his masterwork Genes and Spirits, he explores South Africa’s Jazz history, while also fusing it with club music, Afro-Cuban traditions, rocksteady, and R&B. A particular surprise comes at the end, when Cuban virtuoso Chucho Valdes joins Moses in a piano duet on “Ntate Moholo.”

iTunes | Spotify | Apple Music

Basil Coetzee, Sabenza

Famed for his solo on Abdullah Ibrahim’s Mannenberg (so much so that he began to go by the nickname “Mannenberg”!), tenor saxophonist Basil Coetzee recorded several solo albums of his own. His finest, however, is this 1987 outing featuring his group Sabenza. The frontline of Basil and altoist Robbie Jansen is gripping and thrilling as they wend their way through up-tempo masterworks like “Khayelitsha Dance” and “African Jazz Dance,” as well as slower anthems like “CT Blues.” Released on the independent label Mountain Records, it is a stellar example of Cape Town’s Jazz scene at the time.

iTunes | Spotify | Apple Music

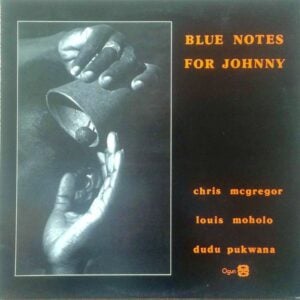

Blue Notes, Blue Notes for Johnny

One of the most influential groups to emerge from South Africa, the Blue Notes were an integrated ensemble that formed under the leadership of pianist Chris McGregor. Initially featuring trumpeter Mongezi Feza, altoist Dudu Pukwana, tenor Nikele Moyake, bassist Johnny Dyani, and drummer Louis Moholo-Moholo, the band offered a truly unique vision for the genius of South African Jazz, bridging the worlds of Duke and Monk with the worlds of Ornette Coleman and Albert Ayler, all the while infusing the music with Xhosa traditions. Though the band would ultimately disband after they arrived in Europe, they would at times regroup for shows. This album, recorded after the death of Johnny Dyani, is utterly haunting. The Blue Notes, now a trio following the deaths of Feza, Moyake, and Dyani, play with unrelenting intensity, most perfectly captured in their unforgettable rendition of the South African standard “Ntyilo Ntyilo.” The album represents why the Blue Notes (and a descendant group of it, The Brotherhood of Breath) were so influential in Europe’s Jazz scene.

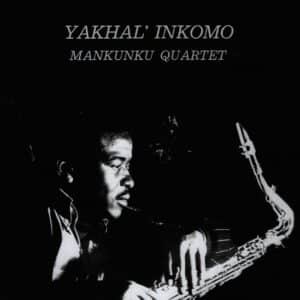

Winston Mankunku Ngozi, Yakhal’ Inkomo

For many, Winston “Mankunku” Ngozi’s 1968 album Yakhal’ Inkomo is the most influential Jazz album in South Africa’s Jazz scene, the equivalent in influence for South Africa’s Jazz scene that John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme had for America. It is therefore somewhat shocking that an album so influential is almost unknown outside of South Africa. Hearing the album, particularly its title track, was a life-changing experience for many. Mankunku’s horn playing, intensely lyrical and questing, stands as the gold standard for a South African approach to tenor playing, one heard in the sounds of his contemporaries like Duke Makasi, as well as succeeding generations of artists, from McCoy Mrubata to Linda Sikhakhane.